Thanks to OLED and “dark-mode” being trending, I’ll bump this posting back up!

On OLED displays using dark-mode lowers the energy consumption.1 Beside the personal preference this is the reason, why the dark-mode and dark themes for websites are becoming more common. This means, that if we want to display visualizations on such websites, we should consider it being “dark-mode-friendly”.

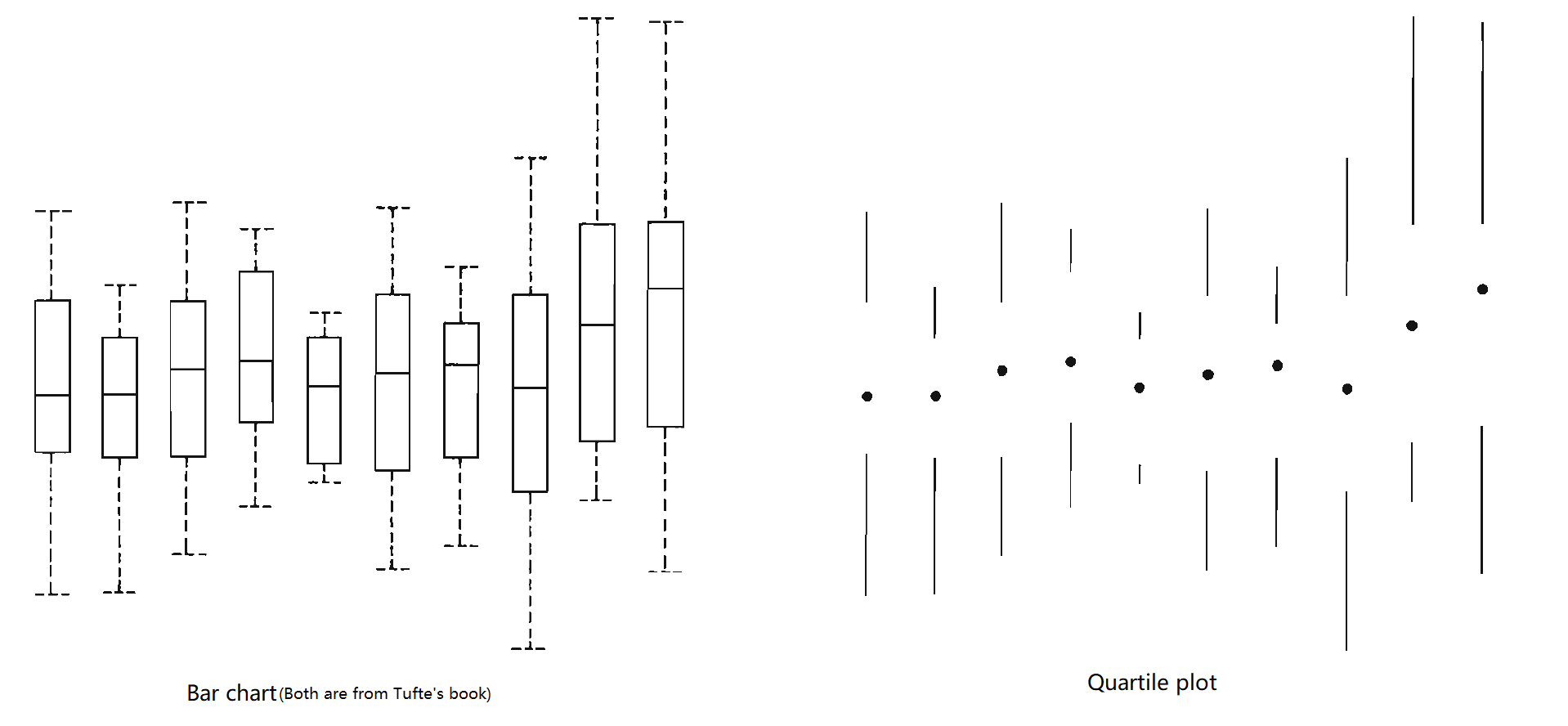

If we still want to follow the “Data-Ink Ratio Principle”, we simply switch black and white in our calculations.

The word “ink” seems to be outdated for todays use and I agree with @jamescottbrown that we should use “graphical elements” instead.

Personally I dislike visualizations with high data-ink ratio, since they get “boring” to look at. It seems that this isn’t only true to me, since Inbar did an experiment on students, that report the same preferences as me.2

Humans like beautiful things, studies show, that our well-being improves, when we look at beautiful things. Less boring things increases our attention.3

So what should we call “chartjunk”? For me chartjunk is everything that takes the locus of attention away from the data or/and obscures it.

So instead of using quality metrics, in this case it would make more sense to discuss your result with the target users.4

As conclusion, please be creative by designing visualizations!

Sources

1:

https://www.howtogeek.com/407860/heres-when-a-dark-theme-can-save-battery-power/

2:

Ihad Inbar, Noam Tractinsky and Joachim Meyer. Minimalism in information visualization: attitudes towards maximizing the data-ink ratio. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1362587.

3:

https://youtu.be/-O5kNPlUV7w by Kurzgesagt, they create beautiful videos with a lot visualizations in it.

I recommend watching the whole video, but the important part starts at 4mins.

4:

“Evaluating visualizations” slides page 29 by Chat Wacharamanotham from University of Zurich.